An experimental gene-therapy treatment for Parkinson's disease has eased the movement problems of a small number of patients and raised no major safety concerns. The study, reported in The Lancet Neurology1, is the first double-blind clinical trial to show a benefit of gene therapy to patients with the neurodegenerative condition.

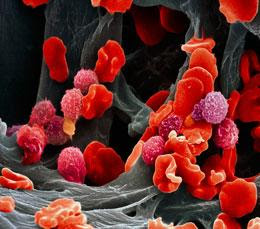

Parkinson's disease is characterized by tremors, slowness and cognitive problems, and is caused by the death of neurons in brain circuits that makes dopamine. The effects cascade through interconnected brain regions involved in movement, with some areas becoming overactive.

Many patients are treated with the drug levadopa (L-DOPA), a chemical precursor of dopamine, and regain control of their movements. Over time, however, patients become less sensitive to L-DOPA and burdened by its side effects, which include psychological and physical problems.

Long-term fix

Gene therapy could offer a longer-lasting solution, says Andrew Feigin, a neurologist at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who led the trial along with Michael Kaplitt, at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York and Matthew During, at Ohio State University in Columbus. This involved 45 patients aged between 30 and 75 years old, and was funded by Neurologix of Fort Lee, New Jersey, which holds the patent for the therapy.

Half of the patients received an infusion of a virus engineered to deliver a gene called glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) into a brain centre that is overactive in Parkinson's disease — the subthalamic nucleus. GAD encodes a neurotransmitter called GABA, which quiets neurons in this area. Another treatment for Parkinson's, deep brain stimulation (DBS), uses electricity to silence neurons in the same region.

The remaining patients underwent brain surgery, but did not receive the gene therapy.

Six months after these surgeries, Feigin's team measured improvements in both sets of patients using a standardized assessment of Parkinson's disease that looks at factors such as gait, posture, and hand and finger movements. Patients who had received the gene therapy exhibited a 23.1% improvement on this scale, compared with a 12.7% boost for patients who had undergone the placebo surgery. However, patients given the gene therapy did not, as a whole, see any more quality-of-life benefits than the other group.

Feigin's team excluded six patients who may not have received the gene therapy because of problems in its delivery. He says that this is justifiable in a small trial intended to test whether or not a treatment works. "If you included people who didn't get the therapy it could easily wash out the benefit you might see," he says.

In safe hands

One patient who received the gene therapy required treatment for a bowel obstruction 4 months after surgery, but Feigin says this was not related to the therapy.

"I'm very excited to see that it's safe," says Stéphane Palfi, a neurosurgeon at Henri Mondor Hospital in Creteil, France who was not involved in the trial.

However, he notes that DBS typically offers much more benefit to patients with Parkinson's disease. And, he adds, unlike gene therapy, DBS can be tuned up or down depending on a patient's current condition.

Despite this, Palfi remains enthusiastic that gene therapy could provide another tool with which to manage Parkinson's disease. He is involved in an early-stage safety trial for delivering genes involved in making dopamine to the brains of patients with Parkinson's disease. Palfi says that, so far, nine people have received the treatment.

Other scientists are testing gene therapies that prevent neuron from dying in patients with Parkinson's disease.

Marc Panoff, chief financial officer at Neurologix, says that the company will seek permission from the US Food and Drug Administration later this year to conduct a larger clinical trial.

Source: http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110317/full/news.2011.167.html